JEWISH LIFE

From Pack Peddlers to Professionals

Consultant: Robert S. Schine, Ph.D., Curt C. and Else Silberman Professor of Jewish Studies, Middlebury College, Middlebury, Vermont

Central & Eastern European Jewish Experience

Culture and Identity

Like Jewish immigration to America in general, the Jewish immigrants to the Slate Valley in the 19th and early 20th century came in two waves: the German Jews, from central Europe, who began to arrive in significant numbers in the 1830s and 40s, and the Jews from Eastern Europe who immigrated from the 1880’s on through the First World War. The German Jews were reacting to a resurgence in anti-Jewish sentiment, as well as a declining economy. The Eastern European Jews were reacting to the discriminatory decrees of the Czarist regime, the “May Laws” of 1882, and to the mob violence—the

pogroms—to which they were exposed.

Until the era of Emancipation, the gradual concession of civil equality to the Jews beginning toward the end of the 18th century, Central European Jews had been confined to the Jewish quarters, or “ghettos” of their cities. The Jewish community was separated, distinct in customs, dress, and language from the Christian majority. In everyday life they spoke Judeo-German, a German dialect also called Yiddish, written using the Hebrew alphabet. Hebrew, the holy tongue, was the language of prayer.

However, with the Emancipation, the gates of European society opened, and Jews were quick to embrace European culture. Standard German began to replace Judeo-German. Debates on religious observance erupted as reformers argued that many Jewish practices were no longer meaningful, while traditionalists sought to resist changes for which opportunism seemed to be the real motive. Reformers sought to make the synagogue more decorous, introducing organ music, or advocating the use of German alongside Hebrew in worship. Some Jews, for whom Judaism seemed only an impediment to their integration into Christian societies, converted to Christianity. Baptism represented, in a quip attributed to the poet Heinrich Heine, “the ticket of admission” to European civilization.

When conservative reaction swept through Europe following the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte, many of the gains of Emancipation were reversed and hopes of integration were frustrated. Anti-Jewish mob violence, the Hep-Hep riots of 1819, swept across Germany. Although the authorities intervened, some pointed to the riots as proof that Emancipation was premature. Following the failed liberal revolutions of 1848, German-Jewish immigration to America reached its height, as did German immigration altogether.

Eastern European Jews, by contrast, continued to endure the anti-Jewish policies of the Russian Empire, punctuated by interludes of greater toleration. Many Eastern European Jews lived in small cities and towns—a shtetl in Yiddish—in which Jews made up a substantial proportion of the population and infused the town with a Jewish character, the kind of town romanticized in the musical “Fiddler on the Roof.”

Throughout the 19th century, Jews could reside legally only in a region of western Russia known as the “Pale of Settlement” and in the Ukraine in the south. Popular anti-Semitism was skillfully exploited by the Czarist government to deflect political discontent from the regime and channel it toward the Jews. Following the assassination of Czar Alexander II by revolutionaries in 1881, Anti-Jewish sentiment reached a crescendo, and rioting broke out against the Jews throughout the Ukraine, under the watchful and indifferent eyes of the Czarist police. These bloody riots, or pogroms, continued into the 20th century. The most notorious, the pogrom in Kishinev in 1903, evoked revulsion abroad, and has been commemorated in an agonized poem in Hebrew by Chaim Nachman Bialik, “In the City of Slaughter.” Other pogroms are remembered in the family histories of the Jews of the Slate Valley.

In the stratified society of Czarist Russia, the Jews were also a distinct group, separated by religion, language, and mutual suspicion. Unlike the Jews of Central Europe, the Jews of Eastern Europe retained Yiddish as their vernacular. By the end of the century, Yiddish writers were producing works of poetry, fiction, drama, translations of European classics, and works of scholarship. Their culture was always multi-lingual: Yiddish was the vernacular, Hebrew the language of prayer and learning, and Russian, Polish, Ukrainian, or Lithuanian the language in which Jews dealt with others.

Education

The morning prayers of Jewish practice contain a blessing that lists the deeds for which reward is stored up in this world and in the hereafter, and then pronounces, “But the study of Torah is equal to them all.” Learning is at the core of Jewish life. In both central and eastern European communities, the study of Torah began early in childhood, and, for the able, continued through a yeshivah, an academy in which young men seek to master the texts of the rabbinic tradition. To be sure, women were neither offered nor expected to attain the same level of education. For them, books of women’s devotions and blessings were printed, as well as collections of rabbinic lore, in Yiddish, not in Hebrew.

With the advent of Emancipation, some progressive Jewish schools combined Jewish and secular learning. In the 19th century, universities began to admit Jews to higher education. However, the change of climate was less perceptible to Jews in the small towns and villages, such as those that the immigrants to the Slate Valley had left behind.

Toward the end of the 19th century, the proponents of Zionist culture founded schools in Eastern Europe in which Hebrew was consciously and deliberately used as the language of instruction and a full range of subjects were taught. Yiddish, on the other hand, was still considered the national language of Eastern European Jews. For the majority of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, however, education had started in the cheder, a simple, crowded room with a tutor, and continued, for the fortunate, in a yeshivah.

Economics

In central Europe discriminatory laws limited the choice of occupations by which Jews could earn a livelihood. Forbidden from owning land and barred from the guilds, Jews had, perforce, adopted trade and money lending as their main means of support. Undoubtedly, this involuntary limitation fueled the stereotype of Jews as unproductive moneylenders and middlemen. As the Jewish savant of Berlin, Moses Mendelssohn, summarized the dilemma, “First they tie our hands, only then to accuse us of not using them.” As Emancipation progressed in the nineteenth century, Jews could take up other occupations, but the economic slump of mid-century, along with the resurgence of anti-Jewish bias, did its part to encourage Jews to seek their fortunes elsewhere.

In Eastern Europe, Jews engaged in a wider range of occupations, as tradesmen, merchants and innkeepers, to name some. But poverty was widespread, and was, in the view of some historians, as strong a motive as the legal harassment by the Czarist regime or the pogroms for seeking better opportunity in America.

The American Jewish Experience

Cultural and Identity

The German Jews in rural areas like the Slate Valley sought to maintain the customs familiar from home in their new surroundings. Occasionally, as one New York rabbi observed, the loneliness of these itinerant peddlers kindled a deeper desire for Jewish community than they had felt in Germany. This seems to have been the case for the first Jews of the Slate Valley, the itinerant peddlers who gathered in Poultney every Shabbat and on the Jewish high holidays of the New Year and the Day of Atonement, in order to assemble the required minimum of ten for services (a minyan), and to enjoy the fellowship of other Jews. Among themselves they spoke Judeo-German, and in religious custom, they sought not innovation or reform, but continuity.

For the Eastern European Jews who arrived from the 1880s on, the situation is more complex. Even though the sheer numbers of Jewish families in the Slate Valley increased, it remained a backwater on the Jewish map. The Poultney congregation had dispersed, and the nearest communities with a synagogue, a rabbi, or a religious school were Glens Falls and Rutland. Unlike peddlers, who could break their routine for the Sabbath, the Granville merchants felt compelled to do business on Saturdays, the main shopping day for their customers. Commitment to Jewish traditions ranged from strong to

tenuous.

But despite stratifications in economic status and in differences in religious practice, the Granville Jews stress that their common identity as immigrant Jews bound them together. Furthermore, they embraced the liberties of American citizenship, serving their communities and serving their country with pride, as many of the pictures in this exhibit attest. Nonetheless, an uneasiness about the persistence of Anti-Semitism remained. Some Granville Jews report paying Anti Semitism no heed even when it surfaced. To generalize, the Jews of the Slate Valley, like their coreligionists elsewhere, rewarded

their acceptance into American society with deep loyalty to America and pride in its democratic ideals.

But a lingering wariness about their acceptance into the American mainstream could not be suppressed. It is evident in the report of the founding of a regional post of the Jewish War Veterans of America, attended by Jewish veterans from throughout the Slate Valley. Alluding to the resurgence of Anti-Semitism, the keynote speaker at the ceremony stated that the primary activity of this national veterans’ organization was “to combat subversive elements trying to introduce various ‘isms’ into our great country.”

The Americanization of succeeding generations proceeded apace. Yiddish language became a subject of fond reminiscence, but is no longer a living language among the generation born in America. In the Slate Valley, the Jewish population has dwindled to an isolated few, with no organized Jewish communal life of any kind. The paths taken by Granville families track with trends in American Jewry as a whole. Some families have maintained Jewish customs. Many embraced either the Conservative or the Reform movements within American Judaism. Many have married partners of other faiths, a

trend that, according to a 1992 study, accounted for over half the marriages of young Jews.

Education

Once in America, Jewish children could attend public schools. With no English, children of nearly any age were often placed in kindergarten, and raced through the grades as their language skills caught up with their age. The children of the Jewish families of Granville were full participants in the Granville High School, many of them excelling academically and on the playing field.

Religious education required special efforts. Some families sent their children to Rutland for lessons with the rabbi. Other families banded together to dispatch a taxi to Glens Falls every Sunday morning to transport their children to religious instruction with the rabbi there.

The generation of immigrants established a foundation of economic stability that their children were expected to use as a way station to a higher level of education than that of their parents. Their children, in turn, are indistinguishable from other children of opportunity in America.

From high school, the majority of the children of Granville’s Jewish immigrants went on to higher education, to degrees in business and in the professions, launched on trajectories that would lead most of them away from small town life. The memoirs of Granville’s Jews proudly report on the academic achievements and honors, the professionals and academics among the third and fourth generation, since pack peddlers first started plying their trade in the Slate Valley.

Economics

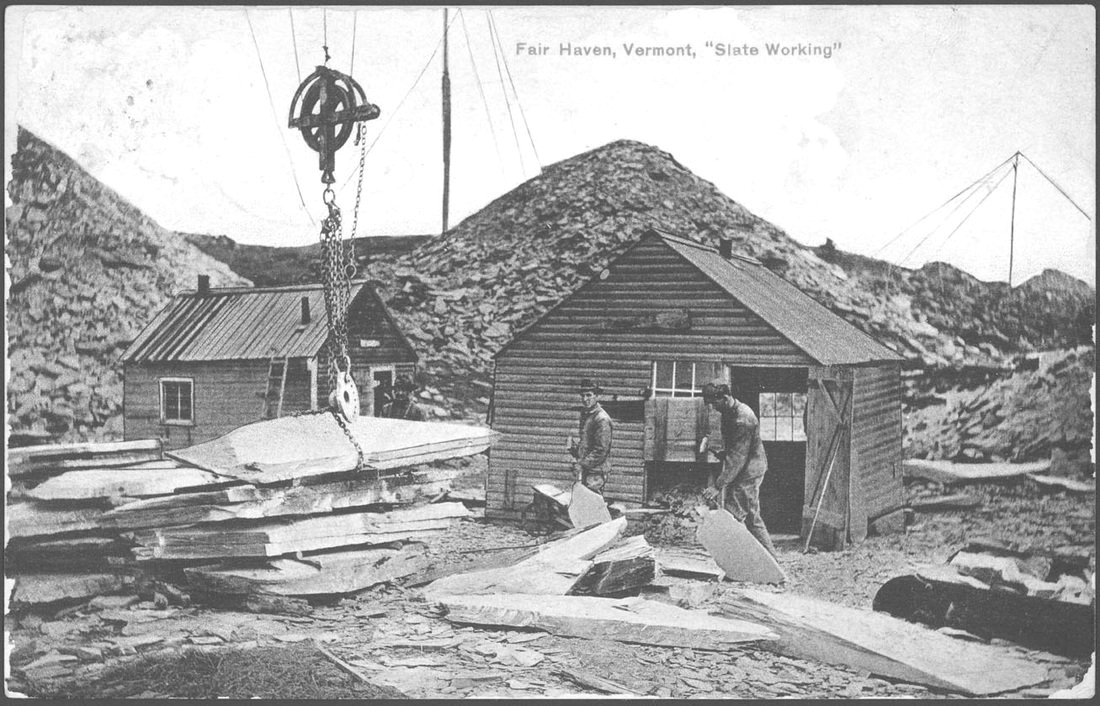

Unlike the Eastern European Jewish immigrants in the large cities of America, there was no working class among the Jews who settled in small town America. They were entrepreneurs who started as pack peddlers and advanced up the ladder of the commercial sector. Venturing forth from their ports of entry, they sought promise of a decent livelihood. The Slate Valley offered precisely that opportunity. Jewish merchants sold the Welsh, Irish, Italian, Slovak, and Polish workers and their families everything they needed, from work boots to groceries. Except for the case of Siegmund Weinberg, who leased lands to quarry operators, no other Jews are known to have been directly involved in the slate industry. Theirs was a supporting role.

The Jewish wholesalers, retailers and peddlers formed a network connected by business and family ties that were often indistinguishable, providing goods to peddlers, employment to newcomers, and often a stake to those starting out on their own. In the first half of the 20th century, businesses owned by Jews were a dominant presence, or could seem to be, in many small towns across America. Granville was no different: there were at least ten businesses from groceries to five-and-tens to department stores on or near Main Street owned by Granville’s Jews. By the end of the 20th century all of these

businesses had closed, the last of them succumbing to the competition of shopping malls and superstores. The economic role played by Jewish merchants in small-town America belongs to the past. The professional aspirations of the descendants of the Slate Valley Jews drew them to the larger towns and cities. Jews no longer fulfill any particular economic niche in the American scene, but are fully integrated into the professions, the arts, politics, academia,

and business. In short, at no time in the history of the Jews has a community enjoyed such security and success as in contemporary America, in marked contrast to the violent end, in the Nazi genocide, of the Jewish communities the first Slate Valley Jews had left behind. The vanishing of the Jews of the Slate Valley is therefore not so much a sign of decline, as it is a result of the thorough realization of the dreams of its first Jewish immigrants.

Jewish Families of Granville, NY

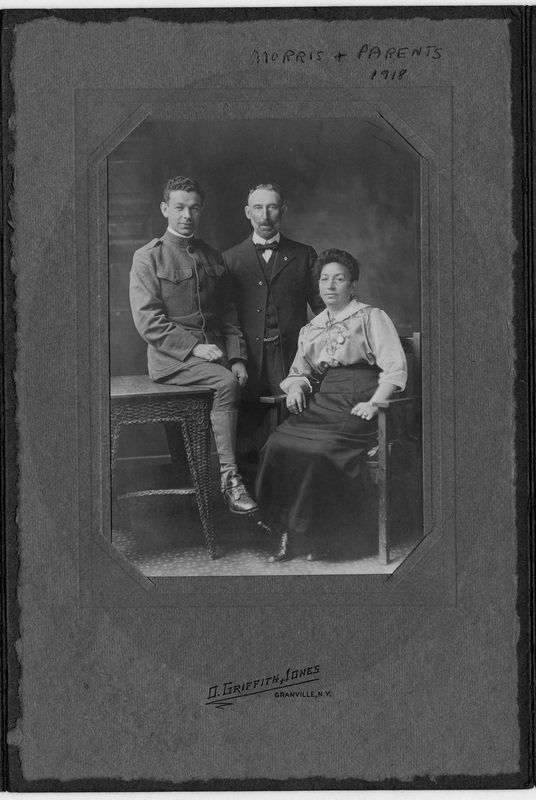

The Rote-Rosens

Morris Rote-Rosen was a beloved citizen of Granville and the Village Clerk for over 50 years. He was born in Mariampol as Meisha Roterosen (the family name was hyphenated after immigration to America), one of five children of Abraham (Abram) and Hayya Reizel (Rose) Mevzos. Not far from Warsaw, Mariampol had a sizable Jewish population—one third of the town total of 6,300 in the 1890s. It was thus a shtetl, the Yiddish term among Eastern European Jews for a small town with a significant presence of Jewish life.

According to Morris’ recollections, his father Abram managed to obtain contracts to supply provisions to the Russian army barracks and kerosene for the city streetlights. He refused an assignment with the Russian secret police, once he learned that he would be obligated to meet a quota of two arrests of revolutionaries each month. He had hoped, in vain, for a special passport to allow him to do business in the interior of Russia, which was otherwise closed to Jews. After losing much of his fortune in a failed lumber partnership with his brothers-in-law, he decided to follow the urging of his brother Leib (Louis), who had been writing encouraging letters home from the marble town of West Rutland where he ran a grocery and dry goods store. Abram arrived there alone in the winter of 1901 and became a pack peddler covering a route through the Vermont marble quarries of West Rutland and Proctor.

Morris Rote-Rosen recalls those years in Mariampol: he and his four sisters were educated by private tutors, since Jewish children were not allowed in the town’s schools. They received religious instruction in a school called a Talmud Torah. In 1903, Morris and his oldest sister Gussie were smuggled out of Lithuania by their Grandfather Mevzos to join Abram in Vermont. Knowing English, he started at the West Rutland school in kindergarten at age thirteen, and finished the year in the fourth grade.